Heel Height: The Deciding Factor 10-13-05 (with 2018 edits) Pete Ramey

Note: If you are new to hooves

and the terminology used here, as a prerequisite, read the

12-article series

http://www.hoofrehab.com/HorsebackMagazineArticles..html

. Written for lay horse owners, these

Q&A-style articles provide a good introduction to hoof care and

rehab.

When horses are in

motion, it is important that they impact with the feet flat with

the ground at the walk. At faster gaits, including a fast,

animated walk, they should land distinctly on their heels.

Almost every energy dissipating feature of the foot requires

this use of the back of the foot to function properly.

The horses' primary energy

dissipaters – the frogs, digital cushions, lateral cartilages,

the bars and the cushioned design of the solar corium are

pretty-much out of function if the horse is carrying its weight

on the toes.

Toe-first impacts

are not always the bad guy, though. Horses use them to negotiate

slick terrain, to accelerate, and to go uphill. The big problems seem to occur –

navicular damage, tendon damage, ligament damage, lamellar

separation, P3 remodeling, solar corium damage, joint problems,

the list goes on – when toe-first is the predominant or only way

the horse moves. In addition to these local problems with

toe-first impact, this compensative movement pattern wreaks

havoc with the entire locomotion system of the horse, often

causing a wide range of issues from teeth to tail.

Domestic horses tend

not to get enough movement and heel-first impact to develop the

lateral cartilages, the digital cushions and frogs into the

strong, shock absorbing tissues they would have become if the

horse was running wild. This soft tissue is supposed to make up

around 60% of the total mass of the hoof capsule if fully

developed (Robert Bowker, VMD). Instead, in many domestic

horses, this tissue is a fraction of the mass and density it

would be in a healthy state because the caudal foot has not done

enough work required to achieve healthy development. The soft

terrain that our foals are raised in, little reason to move more

than a mile or so per day, plus traditions of failing to

routinely trim foal hooves each contribute to this common lack

of internal foot development we see in domestic horses. Failure

to trim is the easiest of these pitfalls to avoid. It doesn’t

seem to matter how much a horse moves – if the frog is lifted

off the ground by excess wall growth, the caudal foot will

become atrophied and over-sensitive.

The result is that

most domestic horses are wimps when it comes to slamming the

back of the foot into hard ground at impact as nature intended.

Given the cost of what this can mean to the horse, one of our

primary roles as hoof care providers is to ensure that the horse

can land heel-first in its turnout environment and in the riding

environment. This is the key to developing a more robust caudal

foot, and is also a primary key to healthy lamellar attachment

and sole thickness at the toe.

A lot of us were

trained to set heel height based on achieving certain palmar

angles. I, like most practitioners, believe that a 3-5 degree

(positive – higher in back) palmar angle is natural for most

horses. But the smart practitioner will understand that horses

do not wreck themselves, or heal themselves, while standing

still on the radiograph block. Indeed they wreck themselves and

they heal themselves while moving, right? So why prioritize the

way the horse stands?

In many horses, if

there is inadequate internal foot development, tight flexor

muscles, or perhaps just a painful case of thrush, if you lower

the heels until the horse has a 5 degree palmar angle, while

standing on the radiograph block or trimming mat, he will just

land on his toes (or side load) to avoid pain when asked to

move. Understand that this may mean that they stand around with

a 5 degree palmar angle but impact the ground at a 25 degree

palmar angle in motion. These should be

frightful mechanics in anyone’s book, as it rips the horse

apart.

So what if, instead,

you were careful not to lower the heels so much that the horse

needed to toe-load. The idea is not to lift the frog off the

ground, but instead to relieve some of the pressure on the frog

as the heels sink into the ground – to reduce the frog pressure

down to an amount that the horse can actually bear. Can you

imagine a scenario, that then, while you might leave the horse

standing around with a 15 degree palmar angle on a hard surface,

that the resulting heel-first movement would yield a ground

parallel P3 at impact? This should be much better mechanics in

anyone’s book.

Heel height (and

thus palmar angle) should be thought of and addressed in motion,

not on the trimming mat or radiograph block. Rule #1:

Trim the heels as

low as possible without causing compensative toe-first impact.

Sole Thickness

When you peel the

hoof walls off a cadaver as in Figure 1, a few things become

clear. The coffin bone (P3), forming the foundation of the front

half of the foot and the lateral cartilages forming the

foundation for the back half of the foot hook together in an

arched shape when viewed from the side. It is the front half of

this arch that gives P3 its positive palmar angle, and this arch

should probably press out flat at peak impact loads under spring

tension – absorbing shock and springing the horse into the next

stride. When the lateral cartilages are weak or under-developed,

this arch has a “flat tire,” leading to zero degree palmar

angles. To reverse this, again, put the back of the foot to

work, thus developing the strength and integrity of the lateral

cartilages and thus creating the coiled spring this tissue is

supposed to form.

Covering the bottom

of this foundation should be a springy, hydraulically dampened

solar corium and a heavily callused sole that is uniformly

5/8”-3/4” (15-18mm)-thick. This is the one non-negotiable part

of hoof health. If the sole is compromised (most often by

routine trimming, sometimes by excess wear, nutritional or

disease/health issues), internal destruction will follow. This

leads to another finite rule #2 for heel height:

Do not thin the

sole beyond its 5/8”-3/4” (15-18mm) natural thickness.

But…

there are a number of horses that do callus at around 1/2"

(12mm) sole thickness and the sole will not get any thicker.

These horses tend to do fine, and you shouldn’t worry much about

them. But don’t take this to mean it is okay to trim thicker

soles down to 1/2" thickness – it is not. Doing so removes

important external callusing, and there is a huge difference

between 1/2" of callused sole and a 1/2" of raw,

freshly-trimmed, uncallused sole. The latter is providing a

fraction of the protection.

Hoof Wall Growing Past the Sole

Another variable

that affects heel height is how much heel wall you allow to

remain standing proud of the sole plane. Some horses do well

with the heel wall trimmed almost down to the level of the sole

plane. Others will go better if you leave 1/4" (6mm) of wall,

sometimes more, standing longer than the sole plane. This will

vary with terrain, plus internal and external frog health and

should be considered while watching the horse move in its

turnout and riding environments.

If a horse is moving

toe-first in the turnout environment (I tend to boot/pad these

compromised horses for the riding environment), I keep letting

the heel walls grow longer past the sole until, 1) heel-first

landing is achieved, or 2) the heels try to distort (roll under,

crush or under-run). I do know a trick to largely prevent this

distortion (see figures 2 and 3). Meanwhile I am simultaneously

doing everything I can to allow the horse to be able to bear

more caudal foot pressure: treating any infections in the frogs,

preserving frog callus at trims, riding or exercising often in

boots with padded insoles to develop the internal structures,

providing deep beds of pea gravel in loafing areas (also to

develop the internal foot and to callus the sole and frog).

Over time, as the

internal foot strengthens, I usually end up trimming the heel

walls almost to the level of the callused sole plane. But the

path to that point usually involves leaving the heels longer for

a while, as heel-first impact in the turnout environment is one

of the major factors involved in bringing a foot to that level

of health internally.

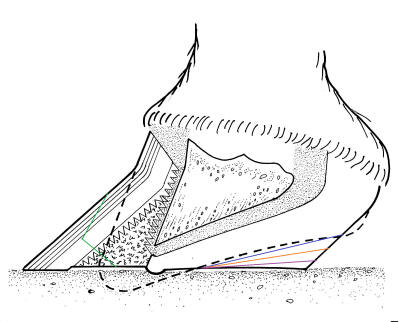

Figures 2 and 3

When the frog is

weak and a longer heel height is needed to allow heel-first

impact, I allow the walls to grow longer at the bar/wall

junction only. Taper the bars up to this higher point as well

(to provide a “brace” or strength to this area), then rocker the

heel wall behind the bar/wall junction. This will allow you to

build as much as 1/2" (12mm) of extra wall height at the

bar/wall junction (even on hooves that want to under-run or fold

underneath the horse) without distortion. You can bring

weight-bearing back to normal proportions without sacrificing

vertical height (Figures 2 and 3).

If this looks

strange to you, it is probably because you are still thinking of

horses’ hooves standing still. When you think of horse hooves in

motion and landing heel-first, this trim starts to make more

sense. I use this method to reverse under-run heels (sometimes

it works in minutes as the now unsupported bent tubules drop

toward the ground), but also do a similar rocker on club feet to

encourage stride lengthening and stretching of the limb.

This is a powerful

tool to both encourage and allow heel-first impact and comfort.

Figure 4

Previous chronic

toe-walker with trim now yielding comfort and correct movement.

The heels have been allowed to grow longer at the bar/wall

junction, but then were rockered behind that point. This both

sets the hooves up to receive heel-first impact while providing

the extra protection needed for this horse to bear pressure on

the weak frogs and digital cushions. In a nutshell, it allows

you to build extra heel height without allowing the heels to

migrate forward.

Flexion, Stance, and Movement

When deciding on the

heel height to set up on an individual horse it is also

important to consider the current flexion, stance and movement

of the horse. This should be a big factor for all horses, but is

particularly critical for horses with hoof capsule rotation and

with club feet.

If you walk up to a

horse with hoof capsule rotation and an elevated palmar angle

(Figure 5), always visualize the healthy foot the horse needs to

grow around the existing P3 and lateral cartilages (dashed

line). In some cases, it is the right thing to do to immediately

trim the heels similar to the dashed line on day #1 (this would

be done by trimming the heels more parallel to the ground plane

of the collateral grooves). In other cases, lowering the heels

at all would be devastating to the horse and actually cause

toe-first compensation, probably making the rotation worse.

Figure 5

For discussion

of treatment of the toes (green line) in order to grow

well-connected walls/laminae (dashed line) and the nutritional

factors, read

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Breakover.html and

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Diet.html

. The most

important factor, though, is usually the heel work we are

discussing right here.

In extreme cases, as

an involuntary reaction to foot pain, the flexor muscles often

knot up or cramp, holding the flexor tendons in an extreme state

of tension. We call this condition wind-up. In less

extreme cases, the horse can simply be stiff all over from the

pain and lack of movement. Other times, the palmar angle/heels

have simply been high, long-term, and joints, ligaments, tendons

and muscles have adapted to it. The list goes on, but for this

conversation, understand that it is a mistake to lower the heels

to “normal” on some horses. Sometimes this is very temporary,

sometimes it is permanent (thus club feet belong in the same

conversation).

To sort through what

is right to do to a given foot on a given day, I do a series of

evaluations:

·

Observe the stance.

If the horse prefers to stand with the limbs vertical or

slightly back, I tend to be more conservative with heel trimming

(purple line). If the horse prefers to stand with the limbs out

front with weight rocked back on the heels, I would lean towards

a more aggressive approach (blue line, or perhaps orange line if

the frog was also weak or infected and sensitive).

·

At the walk, I look

for similar: If the gait is stiff, short, upright, I would lean

towards a trim similar to the purple line. If the horse carries

the limbs out front and heel loading in yielding terrain, I

would lean toward trimming to the blue line.

·

Offer a forward

stretch of the front limbs. Don’t pull on the limb – simply

bring the foot low and forward as if onto a hoof stand. If the

horse readily straightens the carpus (often called the knee),

and bears down pressure on the straightened limb, enjoying the

good stretch, it is showing you there is definitely flexor

muscle laxity and limb mobility to accommodate a trim to the

blue line. If, instead, the horse resists straightening the

carpus and is slow or refuses to engage in the stretch offered,

I tend to leave the heels alone or trim to the purple line. I

then recommend veterinary evaluation of the limbs, routine

stretching by the owner, professional sports massage/stretching,

and therapeutic exercise.

·

Subjectively evaluate

the frog and digital cushion integrity – how tough is the caudal

foot and how much pressure can this frog bear? If you dump a

horse down onto a weak, thrush-infected frog, he will simply

toe-load (or side-load), which will prevent you from growing out

the rotation and keep you from improving the caudal foot health.

This alone causes me to do a lot of trims at the purple or

orange lines, particularly when the horses are new to my care.

Combine all of these factors into your decisions with comfort and flat/heel-first impacts in the turnout environment as the top priority. Then be critical of the result, always adapting with the current status of the horse. Use boots, pads, glue-ons, etc. if the trim alone fails in achieving the movement goals. See http://www.hoofrehab.com/GloveMod.html for instructions.

Negative Plantar Angles

In hind feet, we often see the opposite problem. The plantar angle may present as ground-parallel or even a negative angle (P3 higher in front than in the back). Unless this was just a blatant trimming error (excess sole thickness left at the toe or excess sole thinning at the heels), this hoof form is generally caused by an incomplete or too-forward hind stride - the hind limbs reach too far forward and/or do not extend far enough behind the horse during locomotion. The list of potential causes for this type of movement is long: compensation for front foot pain, too much stall time with associated general muscle stiffness, inadequate warm-up prior to work, saddle fit issues, rider balance issues, dental issues, unnatural training practices (think big lick training of walking horses or false collection that does not include a rounded back), plus a host of potential injuries to the back, hips, limbs, etc.

Therefore, when faced with a zero or negative plantar angle case, you need to use lateral radiographs and the collateral groove depths (discussed below) to determine if there is excess sole thickness at the toe that needs to be removed, but you also need to get to work trying to find and treat the true underlying cause(s) of the movement pattern that actually caused the problem. I typically request a veterinary exam, plus an evaluation by a sports massage therapist. If there is no injury that makes it contraindicated, daily stretching by the owner, plus cavaletti work and light hill work helps these horses more consistently than any other treatment I have seen.

Heel wedging is often recommended for these horses. If a heel wedge immediately corrects the short or forward hind stride, it is a good thing - this correct movement will ultimately correct the plantar angles and the growth pattern of the foot over time. If, however, the horse continues the same movement pattern after the heels are wedged up, the wedges become dangerous and are not recommended, as they are only serving to increase the stress to the extensor tendons, joints, ligaments, etc.

Hoof/Pastern Axis (HPA)

It is common for

people to believe that heel height should be set based on

aligning the standing hoof/pastern axis (HPA). While I do notice

HPA, it does not factor into my heel height decisions – at

all. To me, the palmar angle and the current position of

the pastern are best treated as separate subjects. Horses with

toe pain tend to lean back, lowering the pastern angle. Horses

with heel pain tend to lean forward, raising the pastern angle.

Horses often have different pastern angles standing alone vs.

standing with a rider on their backs. A horse at rest will

constantly shift the pastern angle up and down. At best, a

straight HPA is a moving target.

Overall, though, I

view setting heel height to correct HPA as one more method that

prioritizes static (standing) mechanics over the dynamic (in

motion) mechanics. I prioritize the way the horse moves over the

way the horse stands in every decision I make. That said, almost

every horse in my care ends up with the HPA in alignment, so

perhaps I am often getting similar information from the dynamic

mechanics that others are getting from the static mechanics.

Measuring From the Highly Mobile Coronet?

One of the most

common and serious problems afflicting horses today is the

routine removal of sole done by a majority of hoof

practitioners. One reason for this is generally because people

are trained to measure hoof length from the coronet/hairline.

The coronet is highly mobile, relative to P3 and the lateral

cartilages, creating massive error involved in making foot

length (heel or toe) decisions based on these measurements, or

in equally common subjective decisions, as in, “That foot looks

too long so I’ll cut it shorter,” etc.

This has thankfully

become more widely understood at the toe, since practitioners

can see it every day in lateral radiographs by evaluating CE and

sole thickness. But it is less commonly understood that the same

thing is happening in the back of the foot – the coronet can be

significantly displaced relative to the lateral cartilages,

making heel height measurements from the hairline misleading.

Figures 6 and 7

Left photo of a foot with almost all of P2 buried in the hoof

capsule. Right photo is the same foot – 12 months later – with

approximately a 10mm improvement to CE (coronet to extensor

process – top of coffin bone – measurement). The need for

adequate sole thickness is identical at both moments in time. If

you trim a foot with a 15-18mm CE (as in the left photo) to

“normal” proportions or toe length, the result would be the

total removal of the sole.

The more accurate

way to measure foot length at the heel or toe is to measure or

estimate how much sole is covering the internal structures.

Where the hairline is currently residing on the limb is an

important, but totally separate subject. See

http://www.hoofrehab.com/DistalDescent.htm

and

for an enlightening internal view of this, read

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Coronet.html.

The most accurate

way to measure sole thickness in the front of the foot is with a

good digital lateral radiograph. As a secondary method with

considerable accuracy when properly applied, you can use the

collateral groove heights off the ground (Figure 8) (see

http://www.hoofrehab.com/HorsesSole.html

for details). In most horses (without

P3 remodeling), if there is adequate sole thickness covering the

outer periphery of P3, the collateral groove at the apex of the

frog will be supported 1/2" to 5/8” (12-15mm) off the ground by

that outer periphery of sole (plus any wall height standing

longer than the sole).

These measurements

have their own nuances and exceptions, but overall are far more

accurate than measuring from the coronet.

Figure 8

At the back of the

foot, radiographs are of little use for determining sole

thickness, as we generally cannot see the lateral cartilages or

the corium on radiographs; so the collateral grooves become even

more important for ensuring that post-trim, there is adequate

sole thickness left and to keep us from being fooled by a

vertically displaced coronet.

Again, there are

variables discussed in other the articles, but most horses with

adequate sole thickness in the back of the foot have collateral

grooves – measured at the deepest point beside the bars – that

are 1” to 1-1/4” (25-30mm) off the ground (See Figures 9 and

10).

Figures 9 and 10

Once you are aware

of heel height in terms of how high the palmar processes and

lateral cartilages are being supported off the ground and/or

simply, how much sole is covering the bottom of these

internal structures, you will immediately start to see the

great range of coronet heights off the ground that are presented

with normal heel height internally. The hairline location

(vertically) really has nothing to do with heel height.

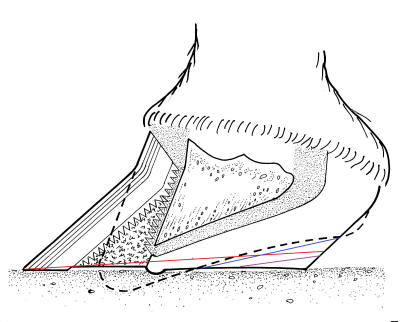

Collateral Grooves and Trimming the Heels Parallel to the Internal Structures

The collateral

grooves can also be used to determine the angles and location of

the internal structures within the hoof capsule and guide you in

trimming more parallel to them. In figure 11, if you lowered the

heels in a straight plane from toe to heel (red line), it would

cause you to excessively thin the already too-thin sole at the

toe.Trimming or shoeing on this plane would also perpetuate the

rotated hoof capsule.

Figure 11

To accomplish this is in the field, hold the rasp “tipped up away from the toe” more parallel to the ground plane of the collateral grooves, rasping the corner of the heel. For example, the Figure 11 drawing would likely have a starting collateral groove depth of 1/8” (3mm) at the apex of the frog and 1-3/4” (43mm) at the deepest point beside the bars.

If, instead, you

chose to trim to the blue line, you would float the rasp above

the toe so that the collateral groove at the apex of the frog is

about 1” (25mm) away from the rasp as you trim the heels down to

perhaps a 1-1/4” (30mm) collateral groove height at the deepest

point beside the bars (or stop the trimming before you would

start to thin the sole that is already the correct thickness,

usually at the widest point of the foot). The bars would then

need to be tapered so that they had at least 1/4" of concavity

or relief at the ends, depending on terrain – usually – Read

http://www.hoofrehab.com/TheBars.htm

and

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Seasons.html

for details.

Change

Every one of the

variables discussed here can and will change over time.

Therefore, it is important that you re-evaluate each one of them

at each trim to keep the heel height optimized at all times.

Generally speaking, to combine the rules from above, we want the

heels as low as possible, without, 1) Causing toe-first

compensation or lameness, or 2) thinning the sole beyond its

normal

5/8” (15mm) callused thickness. We also never want to lower the

palmar angle below 3 degrees or over-stress a compromised limb.

Aside from watching the horse move, also teach clients to look

for compensative movement and report it to you so you can adapt

and adjust. More importantly, look at the wear pattern – look

for excess wear at the toe and inadequate wear at the heels –

this can tell you a lot about how the horse has been moving

throughout the trim cycle and give important clues about

adjustments you should make with the trim.

Figure 12

This foot has

been loading uniformly throughout a 6-week trim cycle – flat at

the walk and heel-first at the trot in the home environment. No

major changes are needed to the heel height – just a routine

trim, uniformly removing 1/8” (3mm) or so of excess wall and

heel height and then a roll or bevel on the walls.

Figure 13

This is the wear

pattern of a horse that has been compensating by overloading the

toes. The front of the sole is worn flat and the wall is worn to

the level of the sole. Perhaps the heels were over-trimmed at

the last visit? Perhaps they should be left longer this trim?

And rockered? Or maybe the horse needs thrush treatment. Perhaps

the limbs are stiff and in need of stretching, warmup, or more

exercise in general? Maybe the horse moves just fine in its

turnout environment but needs boots/pads during riding. Think.

Adapt. Break this Pattern.

All photos are from

Pete Ramey’s files or from the book Care and Rehabilitation of

the Equine Foot. Black and white line drawings by Karen Sullivan

– color graffiti added to them by Pete.

*

*